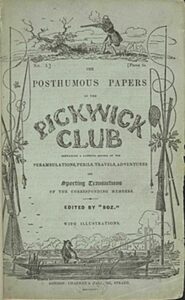

In prepping a blog for National Paperback Day on July 30th, I stumbled across an accounting of how Charles Dickens is credited as being the creator of the paperback book—though of course, they didn’t call them that then. Dr. Elliot Engle has taught at North Carolina State University, written plays, and ten books, but his most lasting fame may come from his mini-lecture series on Charles Dickens that ran on PBS.

Following is a recap of Dr. Engle’s lecture on Charles Dickens:

When Dickens was twenty-three he was a nobody. He had a job that was so boring (a parliament reporter) that at night, he said, to keep his sanity he would simply wander the streets of London and sketch. He didn’t sketch with a pencil, however, he sketched with a pen. He wrote essays, sketches on people and places that caught his eye. Dickens sent his sketches to his favorite magazine; if the editor liked it, he would publish it. The magazine didn’t pay anything; but reward was seeing your words in print.

If you were an unknown like Dickens, you had to invent a pseudonym. Dickens thought up literature’s most memorable disguise—he borrowed the name Boz from his youngest brother, Moses, who was seventeen years younger and had been born with a chronic sinus condition and couldn’t pronounce M. Dickens took Boz from his adenoidal younger brother and put it on every sketch he sent out to magazines.

By the time Dickens was twenty-three, numerous publishers had accepted a total of thirty-six different sketches by him. Everything he sent out was published. Did this make Dickens happy? No, because he wasn’t being paid anything. He then came up with the practical idea of sweet-talking a publisher, John Macrone, into bringing out all thirty-six sketches in a book. So Dickens’s first book was Sketches by Boz, because he was not ‘Dickens’ yet. The book sold poorly, yet its publication was the smartest thing Dickens ever did.

In his day—1836—if a publisher brought out a book that didn’t sell, he could still make a decent profit on it. All the publisher had to do was send a complimentary copy to other booksellers, with an accompanying note that said, in effect, ‘This is one of our hottest best-sellers, but we respect your firm so much we want you to have a complimentary copy.’ Now, every bookseller in England knew what this meant: ‘We cannot sell this turkey. Please, take it off our hands,’ and every bookseller would willingly comply. The important point is that if a publisher was burdened with a book that didn’t sell and was willing to give it away to other booksellers so it could go on the shelf, he received from the British government a tax credit for each book.

So although Sketches by Boz didn’t sell to anyone, it was on every bookseller’s shelf; they knew they had to take in this turkey so when they had a turkey of their own, they could send it on and receive the tax credit. So Sketches by Boz was mailed out to other booksellers, who would put these books on the very top shelf in the back of their bookstore where it wouldn’t take up valuable space, and it would simply gather dust and die a quiet death.

Unbeknownst to Dickens, six months after Sketches by Boz was published and fizzled, the finest illustrator of that era, Robert Seymour, walked into the publishing house of two young, unknown, rather incompetent publishers named Mr. Chapman and Mr. Hall who were about to go bankrupt. They never claimed any good authors among their literary stable, and they never published books that sold respectably.

Seymour approached the penurious publishers with a request that seemed heaven-sent. He had just finished a picture book and wanted Chapman and Hall to publish it. Of course Chapman and Hall were ecstatic; any book with Robert Seymour’s name on the title page would be an instant bestseller because of his reputation. It would save their firm. But they couldn’t understand why the great Robert Seymour had come to them.

What Chapman and Hall didn’t know was that Robert Seymour was an alcoholic, a drug user, and a compulsive gambler. These vices had gotten him into such deep debt that he needed 85 percent of any profits. Chapman and Hall were known to be in dire circumstances, so he told these two young men, ‘I’ll let you publish my picture book, but I need 85 percent of the profits. Is it a deal?’ Chapman and Hall had never had 15 percent of anything; they considered the offer generous and were ready to sign, but Mr. Chapman did say, ‘By the way, Mr. Seymour, what is this picture book you’ve written about?’

Seymour described his work thus: ‘I’ve invented an athletic club, a sports club, but it only has four fat, old men in the club and they’re not athletes at all. They try to skate on the ice—they’re so fat they fall through. They try to shoot a bird—they’re so incompetent they shoot someone’s rear end off by mistake. I’ve drawn one hundred and fifty pictures of these fat and funny sportsmen, and that’s my book. What do you think?’ Well, Chapman and Hall thought it was the silliest thing they’d ever heard of, but they told Seymour in no uncertain terms that it was brilliant. They knew the name Robert Seymour on the title page would guarantee a bestseller. But it was Robert Seymour’s next words that changed the history of British literature:

‘Perhaps if we wrote humorous captions underneath my pictures, it wouldn’t be just a picture book, it would be a joke book and we could charge double. Do you know of some clever young man we can hire for a little money to write amusing captions?’ Chapman and Hall did not know of anyone—which is why they were going bankrupt. But, Mr. Hall tells us later, he was not about to tell Robert Seymour that they didn’t know of some young funny writer because they were afraid they would lose his business.

As Mr. Hall’s gaze went up to heaven to pray, it passed the top shelf at the back of the store, and right at the front of that back shelf, in a red binding, was Sketches by Boz. Mr. Hall told Robert Seymour that they knew someone and just needed a week to get in touch. Which of course meant they needed a week to find out who in the world this “Boz” was. Seymour agreed to wait and left the shop.

As soon as he was gone, Chapman and Hall raced to the bookshelf, took down Sketches by Boz, and frantically, fruitlessly searched for a name they could contact. But of course Dickens couldn’t put his name on the book; it only said ‘Boz.’ And so, as the joke goes, for the next week they ran all over England crying, ‘Who the dickens is Boz?’ Finally Chapman and Hall decided that if they went to the publisher of Sketches by Boz and offered him a little bit more money, perhaps he would share the author’s name. Well, of course Macrone was only too happy, for very little money, to tell them the fateful, red-bound book was by some writer named Charles Dickens.

Thus literary history was made on February 8, 1836 when Robert Seymour, Mr. Chapman, Mr. Hall, and Charles Dickens all met to sign the agreement for the joke book that Seymour would draw and Dickens would caption. Dickens insisted that they all meet at his home. He was insecure and wanted the meeting to take place where he felt most comfortable. When Mr. Seymour launched into his description of the antics of the sports club, everybody assumed Dickens would rejoice. They did not, however, know the twenty-three-year-old Charles Dickens, who wanted control in everything he ever did and wanted it even now.

Dickens said instead, ‘May I have five minutes in my study to consider this proposition?’ He walked into his closet (he didn’t have a study in his apartment, but he didn’t want them to know that). Dickins supposedly took a candle into a closet area, wrote for five minutes, came out, and gave a list of five demands to Mr. Chapman and said, ‘If these five demands cannot be met, I do not wish to work on your project.’

You would assume that Chapman, Hall, and Seymour would in unison have said, ‘Who do you think you are, giving us this ultimatum!’ But Mr. Chapman wisely read the list of demands and found one ultimatum so brilliantly conceived, they knew they would side with Dickens. This fateful ultimatum would change British literature.

Dickens’s idea was breathtaking in the simplicity of its innovation. They would publish Seymour’s idea of four fat, old men as a joke book, which Dickens would write and Seymour illustrate, and charge a hefty price for it. But—and this was the key—they would soften the blow to the reader’s pocketbook by bringing out the novel once a month, three chapters at a time. Then readers would have to come back in February, put down another shilling, and get chapters four, five, and six. And they are going to have to come back again in March, put down another shilling, and get chapters seven, eight, and nine. ‘I will make this novel so long, readers will be buying it for two years. We finally get all of their money; they finally get all of our book.’

Mr. Hall was pessimistic that such a radical notion would work and explained the finances of publishing to Dickens. ‘It costs us a minimum of three shillings a copy to produce any book, even this new once-a-month, three-chapter-at-a-time idea you have. You just told me to sell your book for one shilling a copy. When I sell your book, I lose two shillings each time.’

Dickens said, ‘No, I’ve done my homework and there is a way we can make a fat profit on one shilling.’ When Dr. Engle gave this lecture to his students, he paused here and pointed out that Dickens always did his homework. He walked over to his bookshelf and pulled off a book—any book would do—and said, ‘When someone buys a book, is it not true that whether the book has eight pages or eight hundred pages the reader is not paying for the pages?’

Mr. Chapman agreed. ‘Of course. Pages are made of cheap paper pulp. They cost us almost nothing, so the price of the book is not determined by the pages.’

Dickens said, ‘Isn’t it also true that when someone buys a book, what he is actually buying is the front cover, the back cover, and the spine, because they are made out of wood? The wood is expensive and determines the price of the book.’ Chapman and Hall agreed.

And then Dickens said, ‘Why can’t we invent a new kind of book for my once-a-month, three-chapter-at-a-time idea? This book will have the covers made out of the same thing as the pages—cheap paper pulp. We could call it paperback.’ Thus Dickens, at twenty-three, invented the mass-market paperback book, but this was not what made him rich. That is still to come.

The publisher said, ‘Let’s pretend we invent this paperback book. We could then make a profit on one shilling, but we will still go bankrupt. Everyone will come the first month and buy the first three chapters. Some of them will come back next month and buy the next three chapters. Maybe some of them will come back the third month. But no one is going to come back every month for two years.’ Chapman and Hall maintained the public would get bored with the long, strung-out process and would quit reading. The publishers, however, would be obligated to keep on publishing Dickens’s chapters even though no one was buying them.

Dickens was already one step ahead of them. ‘I guarantee readers will be throwing money at us, more eagerly at the end than in the beginning, because in each monthly installment on the last page, in the last paragraph, something incredible will happen. At the end of chapter three, I’ll have my hero start walking up a very steep cliff, but a formidable root will be growing out of that cliff. My hero, absentminded and near-sighted, will trip over the root and fall off the cliff. But my hero has forgotten to cut his fingernails for five years. As he starts to fall off the cliff, with his last ounce of energy he will grasp a finger hold. So, in the second-to-the-last sentence of chapter three, he will be hanging at the cliff by his nails alone. And in the last sentence of chapter three I’ll have someone start walking up that same cliff, but the reader won’t know if that person is the hero’s friend, who will pick him up and save him, or if he is the villain, who will slash off the hero’s fingers and send him crashing to his death in the ocean below.’ Dickens delivered his last flourish: ‘You know how they find out? The readers come back and put down their money in February and buy chapters four, five, and six.’

With that flash of inspiration, Dickens invented the form that every one of his novels would take. He never published an entire novel first; he always published them once a month, three chapters at a time. Charles Dickens was the first person to come up with the idea of suspense to link together a work of art. He called this principle procrastinated suspense, and that is exactly what it is and has remained for all these years.

Chapman, Hall, and Seymour himself thought Dickens’s inspiration was an idea of genius. The next step was to give this novel approach to the novel a title. Dickens offered, ‘Why don’t we call the sporting club the Pickwick Club? And we want to title the novel so people will know it is coming out for the first time in a new, cheap form of paperback publication. I want to call the novel The Pickwick Papers.’ And they did.

Was Pickwick Papers a success? More than just a little—it was the best-selling novel of 1836. And thanks to Dickens’s idea, it was also the best-selling novel of 1837 because it was still coming out in 1837. In 1900 a survey found that the best-selling novel of the entire nineteenth century was The Pickwick Papers. And by now you probably think you know exactly why it sold so well: because Dickens had invented the paperback and the soap opera—but you would be wrong.

As clever as those two innovations were, The Pickwick Papers sold so many copies not due to what happened before it came out, but to what happened after. You see, for the first time people had to go to the bookstore every month and buy three chapters at a time, over and over. Yet what did they have to show for two years of buying The Pickwick Papers? Nothing. Dickens and the publishers made sure the paper the novel was printed on was of such poor quality it fell apart if you read it too hard. The readers did not care—they were only paying a shilling, they did not expect paper of quality. What bothered them was this: when they had finished Pickwick Papers, they were left with nothing but flimsy, cheap paperbacks.

There were no public libraries at that point; the first public libraries came in the 1890s. The only library was in your house in a room reserved for books. When you finished a novel that you loved as much as Pickwick (and people had loved it, thought it was the funniest thing they had ever read), you put your novel on your mahogany bookcase and displayed it proudly. But now readers had a new problem. All they had from Pickwick was this pile of paper. They tried to put the paperback Pickwick up against their beautiful edition of Pride and Prejudice or their leather-bound Ivanhoe, and it looked terrible. What were they to do?

Dickens, with his big heart, came to the rescue. In September of 1837, when the last three chapters of The Pickwick Papers were published, everyone rushed to bookstores because they were eager to see how Dickens tied the novel all together in the end. But after they had bought the last three chapters of Pickwick, they noticed, on the other side of the bookstore, piled high to the ceiling, leather-bound, gilt-edged, silk-ribbon-marker editions of The Pickwick Papers in hardback. Here was a handsome keepsake, a presentable addition to their bookshelves. So everyone bought the expensive hardback edition of Pickwick when they bought the last three chapters of the paperback.

Charles Dickens is the only author we know of who sold the same book to the same people twice. They had to buy it in parts because they wanted to know what happened next. Then they had to buy the hardback, because they wanted it to display.

Once the hardback edition came out, Dickens began to wonder, ‘Now that readers have bought the hardback of Pickwick, what will they do with the cheap, three-chapter parts they have been buying for two years?’ He knew what they were going to do; they were going to throw them away. People did not throw them away, however, because a few days after the hardback of Pickwick came out, a salesman would knock on the door, ascertain that the people did indeed still have the paperback version and offered a small sum: which was more than the people would have had if they’d thrown the paperback away.

Now why would Dickens’s firm buy back the cheap three-chapter parts of Pickwick Papers? Profit. They bought back the chapter parts, ripped off the front and back covers of each installment, put them together in chronological order, and sewed them into a gorgeous leather spine with a thin twelve-karat gold band around the edge. This “new” version was sold as The Collector’s Edition of Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, and it was advertised as, ‘Printed on the original paper, when this world-famous novel first appeared.’ You may think, ‘Well, surely no one was gullible enough to buy the collector’s edition. For goodness’s sakes, they had bought it in parts, they had bought it in the hardback, why would they need it?’ You would be too hasty. The collector’s edition was hideously expensive, but anyone who could afford to buy it, bought it.

You, the reader, bought the collector’s edition, but you didn’t take it home—you already had one there—you took it to your bank and put it in your safe-deposit box. Dickens was now a world-famous author, and you had the original printing of when The Pickwick Papers first appeared. You had an original work of art. You left the collector’s edition in your safe-deposit box for a few years, and it steadily gained in value as an investment in original art. Anyone who could afford to buy the collector’s edition always bought it.

You realize, of course, what this means: Charles Dickens is the only writer to sell the same book to the same people three times: once in parts, once in hardback, and once in the collector’s edition. It was a moneymaking scheme like no other. Dickens was only twenty-four years old, and he had written the best-selling novel of all time. Dickens earned 68 million dollars as a writer, making him the top-grossing classic author of all time.”

The first installment of Pickwick sold about 500 copies while the last installment sold about 40,000 copies. There were theatrical adaptations before the series was even completed. Pickwick merchandise began to appear. People could buy Pickwick cigars, song books and china figurines.

Interacting with fans was important to Dickens. Even as the 24-year-old author wrote his new episodes, he wanted to hear readers’ reactions and would then build up any fictional character that had piqued interest.

Charles Dickens’s comic novel The Pickwick Papers, often overlooked today as a lighthearted period piece, was once a matter of very serious concern to thousands of fans across the world, some of whom adopted the personas of their favorite characters and founded appreciation societies.