Today is National Paperback Book Day. Surprise: who knew it was so interesting?

Believe it or not, Charles Dickens is credited with the creation of the mass- market paperback that is ubiquitous today. I wrote a prequel to today’s celebration where I gave a shortened version of a lecture by Dr. Elliot Engle, whose most lasting fame may come from his mini-lecture series on Charles Dickens that ran on PBS.

What is a Paperback

A paperback, also known as a softcover, is characterized by a thick paper or paperboard cover, and held together with glue rather than stitches or staples. In contrast, hardcover or hardback books are bound with cardboard (originally wood), covered with cloth, plastic, or leather. The pages on the inside of a paperback are made of a lower grade paper.

19th Century Publishing

The early 19th century saw numerous improvements in the printing, publishing and book-distribution processes, with the introduction of steam-powered printing presses, pulp mills, automatic type setting, and a network of railways.

The early 19th century saw numerous improvements in the printing, publishing and book-distribution processes, with the introduction of steam-powered printing presses, pulp mills, automatic type setting, and a network of railways.

These innovations enabled the likes of Simms and McIntyre of Belfast, Routledge & Sons (founded in 1836), and Ward & Lock founded in 1854) to mass-produce cheap, uniform yellowback or paperback editions of existing works. They distributed and sold them across the British Isles, principally via W. H. Smith & Sons, newsagents found at most urban British railway stations. These paperbound volumes were offered for sale at a fraction of the historical cost of a book, and were of a smaller format (43⁄8 in × 7 in), aimed at the railway traveler. The Routledge’s Railway Library series of paperbacks remained in print until 1898 and offered the traveling public 1,277 unique titles.

Twentieth Century Publishing: Penguin

The German publisher Albatross Books revised the 20th-century mass-market paperback format in 1931, but the approach of World War II cut their experiment short.

It proved an immediate financial success in the United Kingdom in 1935 when Penguin Books adopted many of Albatross’s innovations, including a conspicuous logo and color-coded covers for different genres. British publisher Allan Lane invested his own capital to launch Penguin Books, the first really “respectable” paperback imprint, initiating the paperback revolution in the English-language book.

Lane intended to produce inexpensive books. He purchased paperback rights from publishers, ordered large print runs (such as 20,000 copies (large for the time) to keep united price low, and looked to non-traditional book-selling retail locations. Booksellers were initially reluctant to buy his books, but when Woolworths placed a large order, the books sold extremely well. After that initial success, booksellers showed more willingness to stock paperbacks, and the name “Penguin” became closely associated with the word “paperback.”

What’s important to remember is the cost of books at the time was prohibitive for most people. As mental_floss notes: “In 1939, gas cost 10 cents a gallon at the pump; a movie ticket set you back 20 cents; John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, the year’s bestselling hardcover book, was $2.75. For a nation suffering 20 percent unemployment, books were an impossible expense.”

New Books on the Block: Pocket Books

On June 19, 1939, a man named Robert de Graff launched Pocket Books. It was the first American mass-market-paperback line, and it transformed the industry and became synonymous with paperback books. Starting with a test run of ten titles, which included classics as well as modern hits, de Graff planned to unleash tote-able paperbacks on the American market. But it wasn’t just the softcover format that was revolutionary: De Graff was pricing his Pocket Books at a mere 25 cents.

But de Graff’s business partners at Simon & Schuster were less confident. Even though some European publishers were making waves with paperbacks—Penguin in England and Albatross in Germany—New York publishers didn’t think the cheap, flimsy books would translate to the American market. They were wrong: it took just a week for Pocket Books to sell out its initial 100,000 copy run. Despite industry skepticism, paperbacks were about to transform America’s relationship with reading forever.

If paperbacks were going to succeed in America, they would need a new model. De Graff, for his part, was well acquainted with the economics of books. He knew that printing costs were high because volumes were low. With only 500 bookstores in the U.S., most located in major cities, low demand was baked into the equation.

So de Graff devised a plan to get his books into places where books weren’t traditionally sold. He used magazine distributors to place Pocket Books in newsstands, subway stations, drugstores, and other outlets to reach the underserved suburban and rural populace. But if Pocket Books were going to sell, they couldn’t just stick to the highbrow. De Graff avoided the stately, color-coded covers of European paperbacks, which lacked graphics other than the publishers’ logos. He splashed colorful, eye-catching illustrations on the covers of his paperback books.

So de Graff devised a plan to get his books into places where books weren’t traditionally sold. He used magazine distributors to place Pocket Books in newsstands, subway stations, drugstores, and other outlets to reach the underserved suburban and rural populace. But if Pocket Books were going to sell, they couldn’t just stick to the highbrow. De Graff avoided the stately, color-coded covers of European paperbacks, which lacked graphics other than the publishers’ logos. He splashed colorful, eye-catching illustrations on the covers of his paperback books.

Even with the success of Pocket Books’ test run, hardcover publishers scoffed at the idea of paperbacks for the masses. Still, they were more than willing to sell Pocket Books the reprint rights to their hardcover titles, if only to humor de Graff. For every paperback sold, the hardcover publisher would receive a penny royalty per copy—which it split fifty-fifty with the author. Pocket Books would also make about a penny in profit for each copy sold.

Since de Graff offered refunds for unsold copies, carrying the books was a no-brainer. Americans devoured every 25-cent paperback published. By the time Pocket Books sold its 100 millionth copy in September 1944, its books could be found in more than 70,000 outlets across the U.S. They might not have had the glamour and sophistication of hardcovers, but paperbacks were making serious money. It wasn’t long before other publishers decided to jump into the game.

Penguin Expands to the U.S.

In the late 1930s, Penguin’s Allen Lane met Ian Ballantine, a young American graduate student at the London School of Economics whose thesis examined the paperback business. Impressed by his research, Lane hired Ballantine to launch a U.S. branch of Penguin in 1939, the same year Pocket Books got its start.

At first, Penguin wasn’t much of a threat to de Graff, since Ballantine, with the help of his 19-year-old bride, mainly imported the parent company’s books from the U.K. The covers featured little besides the title, the author’s name, and the Penguin logo, giving them a generic, minimalist look that failed to excite the American market. But as World War II escalated, Lane’s control over U.S. operations became tenuous. Imports from the U.K. were scarce, and the Ballantines took the opportunity to print their own selections under the Penguin banner, adding illustrated covers to compete with Pocket Books.

World War II brings New Technology and a Wider Readership

Workers now in the military or employed as shift workers had more time to read. Paperbacks were cheap, readily available, and easily carried. Furthermore, people found that restrictions on travel gave them time to read more paperbacks. Four-color printing and lamination developed for military maps made the paperback cover eye catching and kept ink from running as people handled the book. A revolving metal rack, designed to display a wide variety of paperbacks in a small space, found its way into drugstores, dime stores, and markets. Soldiers received millions of paperback books in Armed Forces Services editions.

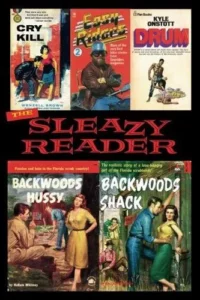

After the war, Lane was horrified to see his prestigious Penguin logo stamped on such tawdry covers. In 1945, he forced the Ballantines out. Lane expected his new hires, German publisher Kurt Enoch and American Victor Weybright, to fall in line with his refined sensibilities, but they too failed him. Graphic (and sometimes lurid) illustrations were necessary for the American market, Weybright argued.

After the war, Lane was horrified to see his prestigious Penguin logo stamped on such tawdry covers. In 1945, he forced the Ballantines out. Lane expected his new hires, German publisher Kurt Enoch and American Victor Weybright, to fall in line with his refined sensibilities, but they too failed him. Graphic (and sometimes lurid) illustrations were necessary for the American market, Weybright argued.

What is a Mass-Market Book?

A mass-market paperback is a small, usually inexpensive bookbinding format. This includes the U. K. A-format books (4 3/8 in x 7 in) and the U. S. “pocketbook” format books of a similar size. They have been historically printed on relatively low-quality paper. They are commonly released after the hardback edition and sold in non-traditional bookselling locations such as airports, drugstores, and supermarkets. as well as in traditional bookstores.

Paperback Gold Rush

With Pocket Books and Penguin paving the way, the paperback gold rush had begun. Other paperback houses soon followed, including Popular Library, Dell, Fawcett Publications, and Avon pocket-size books. In 1948, Lane washed his hands of Penguin U.S., selling the operation to Weybright and Enoch, who renamed it New American Library of World Literature (NAL). Hardcover publishers watched nervously as these new players chipped away at their market share. For the most part, their only stake in the new paperback houses lay in the reprint royalties they split with authors.

Bantam Enters the Fray

Months after his removal from Penguin, Ian Ballantine pitched hardcover reprinter Grossett & Dunlap the idea of starting a new paperback business. Grosset & Dunlap was a joint venture of the day’s biggest hardcover players: Random House, Harper’s, Charles Scribner’s Sons, Book-of-the-Month Club, and Little, Brown. Each of these companies was looking for a way to dip its toes into the exploding market, and Ballantine had come to them at the right time. Grosset & Dunlap, along with distributor Curtis, became shareholders in Ballantine’s new paperback house, Bantam Books.

Bantam’s impact was immediate—its initial printings were usually 200,000 copies or more. Crazier still, almost every title sold out. Each month, Bantam published four new books from the large backlist available via Grosset & Dunlap, and it had no shortage of quality titles, including The Great Gatsby and The Grapes of Wrath (now just 25 cents). How would other publishers keep up?

Bantam’s impact was immediate—its initial printings were usually 200,000 copies or more. Crazier still, almost every title sold out. Each month, Bantam published four new books from the large backlist available via Grosset & Dunlap, and it had no shortage of quality titles, including The Great Gatsby and The Grapes of Wrath (now just 25 cents). How would other publishers keep up?

Paperback Originals

In the United States toward the end of the 1940s, many companies entered the paperback publishing field in the years after Pocket Books’ inception, including Ace, Dell, Avon, Ballentine and dozens of other smaller publishers. At first, paperbacks consisted entirely of reprints, but in 1950, Fawcett Publications’ Gold Metal Books began publishing original works in paperback.

Fawcett was saddled with a distribution agreement that prevented it from publishing and distributing its own reprints of hardcover titles. Seeking to exploit a loophole, editor in chief Ralph Daigh announced that Fawcett would begin publishing original fiction in paperback form beginning in February 1950.

“Successful authors are not interested in original publishing at 25 cents,” Freeman Lewis, executive vice-president of Pocket Books said. Hardcover publisher Doubleday’s LeBaron R. Barker claimed that the concept could “undermine the whole structure of publishing.” Hardcover publishers, of course, had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. They were still receiving 50 percent of the royalties by selling reprint rights.

Fawcett silenced the skeptics by selling more than nine million copies within six months. Authors did the math, and writers of genre fiction—thrillers, Westerns, and romance especially—jumped at the opportunity to write paperback originals. Still, “serious” literary writers insisted on staying in the hardcover market for the prestige, and critics in turn declined to review paperback originals. Clearly, the stigma was still there.

By the 1950s, companies were producing paperback originals in addition to just reprinting classic novels in softcover. Eventually, booksellers got on board, and an industry was born. These days, there are varieties like trade paperbacks and mass-market paperbacks, and most of us find it hard to imagine a time when we couldn’t slip a book in our pockets, purses or backpacks and head to the park or the beach.

Trade Paperbacks

A trade paperback, sometimes referred to as a “trade paper edition” or just as a “trade,” is a higher-quality paperback book. If it is a softcover edition of a previous hardcover edition, and if published by the same publishing house as the hardcover, the text pages are normally identical to the text pages in the hardcover edition, and the book is close to the same size as the hardcover edition. Significantly, the pagination is the same so that references to the text will be unchanged: this is particularly important for reviewers and scholars. The only difference is the soft binding; the paper is usually of higher quality than that of a mass-market paperback, for example acid-free paper. In short, trade paperback books are larger, higher quality, and more expensive, whereas mass-market paperback books are smaller, with less durability but at a lower price.

Literary authors and critics weren’t the only ones turning up their noses at paperbacks. Bookstore owners, for the most part, refused to stock them, and students at most schools and universities still used hardcover texts.

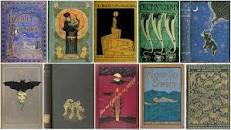

Enter the trade paperback. Publishers had been unsuccessfully experimenting with larger-sized paperbacks since the 1940s, but it wasn’t until Doubleday’s Jason Epstein introduced Anchor Books trade paperbacks in 1953 that the idea caught fire. The idea arose from Epstein’s own college experience. “The writers we had discovered in college were either out of print or available only in expensive hardcover editions,” he wrote in Book Business. Instead of reprinting last year’s hardcover bestsellers and classics, Epstein envisioned a line of “upscale paperbacks” handpicked for their literary merit from publishers’ deep backlists.

Anchor’s trade paperbacks were larger and more durable than mass-market paperbacks and were an instant hit with high schools and colleges. Their attractive covers, illustrated by fine artists, immediately distinguished them from the grittier pulp paperbacks, and they appealed to a more “intellectual” market. As a result, they found a nice middle ground in price. Epstein’s paperbacks had small print runs of about 20,000 and sold for 65 cents to $1.25 when mass-market paperbacks were still going for 25 to 50 cents. Trade paperbacks also opened doors to bookstores. Within ten years, 85 percent of bookstores carried the handsome volumes.

Anchor’s trade paperbacks were larger and more durable than mass-market paperbacks and were an instant hit with high schools and colleges. Their attractive covers, illustrated by fine artists, immediately distinguished them from the grittier pulp paperbacks, and they appealed to a more “intellectual” market. As a result, they found a nice middle ground in price. Epstein’s paperbacks had small print runs of about 20,000 and sold for 65 cents to $1.25 when mass-market paperbacks were still going for 25 to 50 cents. Trade paperbacks also opened doors to bookstores. Within ten years, 85 percent of bookstores carried the handsome volumes.

Paperbacks Take Over Publishing

In 1960, revenues from paperbacks of all shapes and sizes finally surpassed those from hardcover sales. The same year, Pocket Books became the first publisher to be publicly traded on a stock exchange, essentially marking paperbacks’ ascent to the mainstream.

In 1982, romance novels accounted for at least 25% of all paperback sales. In 2013, 51% of paperback sales were romance. Many titles, especially in genre fiction, have their first editions in paperback and never receive a hardcover printing. This is particularly true of first novels by new authors.

Hardcovers have never died out in the United States, though paperbacks continue to outsell them as recently as 2010, thanks in no small part to the continuing price difference—for example, George R.R. Martin’s bestselling novel A Game of Thrones retailed for $32 in hardcover and just $8.99 in mass-market paperback. Today, it’s usual for major publishers to print both hardcover and paperback editions of their books.

E-books

And of course, there’s a new transformation in reading habits: the e-book. Now that Amazon–and the other online booksellers who followed–have untethered e-books from computers by offering inexpensive e-readers, the e-book revolution has done de Graff’s brilliant distribution scheme one better; these days, anyone with a smartphone has an entire bookstore in his or her pocket. The rising popularity of e-books that can be purchased at low cost or borrowed free from the library has threatened the market for mass-market paperback books.

Audiobooks

Originally, audiobooks were started by The American Foundation for the Blind in 1932. New technology gave audiobooks new life when cassettes became available in the 1960s and compact discs in the 1980s. In 1994, Audible made it possible to download books onto desktop computers. Audio is another right granted by publishers where they share profits with authors. As the publishing industry sees an overall decline in physical and e-book sales, audiobook sales are booming. About 55 million people now listen to audiobooks each year. With Amazon Echo and Google Home, people can now do chores or multitask as well as drive while listening to books.

Status of Publishing

Paperback houses are now part of the hardcover publishing empire. At one time, there were names like Little Brown, HarperCollins, William Morrow, Knopf, Doubleday, Simon & Schuster, Random House, Scribner, Farrar Strauss & Giroux, Houghton Miflin Harcourt, Crown, Macmillan, Warner, Viking and, of course, Penguin (and probably others).

Over the years, the number of individual publishing houses dwindled by merger or sale to what was the Big Five, now known as the Big Four since Viacom sold Simon & Schuster to Penguin Random House n 2020. That leaves Hachette Livre Book Group, HarperCollins and Macmillan. Most of the merged companies have become imprints of the other publishers.

What all this means is that there is less competition and variety, as well as lower wages and layoffs. With the latest merger, Penguin HarperCollins now publishes 33% of new books. But as someone else pointed out recently, perhaps we should be more concerned by the fact that Amazon now sells and distributes 49% of them.

(Thanks to Wikipedia and a 2012 article in mental_floss for the history contained herein.)